Iowa might have a new record black crappie — if it passes a DNA test. John Foster was fishing Sundown Lake in Appanoose County on Sept. 24, 2024, when he landed what appeared to be a giant black crappie. The slab measured 18 inches and weighed over 4 pounds, which would make it the new state record for the species. But is it a black crappie?

Black and white crappie can interbreed; the offspring from such a pairing are typically larger than a genetically-pure black crappie. Iowa has records for black and white crappie, but no category exists for hybrids.

“We took a fin clip and we sent it for genetic testing. We’re working with the University of Northern Iowa to identify this fish,” Randy Schultz, Fisheries Supervisor with the Iowa Department of Natural Resources tells Wired2Fish.. “We don’t have any motive other than being able to tell the truth of what this fish is. If it’s a black crappie, we’ll find out. If it’s a hybrid, we’ll find out. Just so we can be honest about the species of fish it is.”

The fish in question is currently finning around a tank in a Bass Pro Shops near Des Moines; it is unclear if that’s where the unidentified crappie will remain. But one thing is certain: John Foster is anxiously awaiting the results of the genetic testing being conducted. It’s a test that could land him in the record books.

JOHN FOSTER’S FISH

The previous Iowa black crappie record, caught in 2013, weighed 3.88 pounds. It seemed like Foster’s fish was a shoe-in for the new record. At least it would have been, if a positive identification could be made. There was even a Facebook post made by the Iowa DNR congratulating Foster on the record, which has since been changed to reflect the fish’s status as a potential hybrid.

According to Outdoor Life, Foster was fishing Sundown Lake, a 400-acre private lake in Appanoose County, southeast of Des Moines. He was targeting a brush pile in 6 feet of water, picking away at crappies with a 1/16-ounce Blakemore Road Runner jig. He hooked a good one, which ran him into the cover and broke him off. So he tied on another and was tight to a good fish almost immediately.

Once it was in his net, he knew he had something special. He rang his brother-in-law and fishing partner Steve Harding, who would meet him at the marina. The pair decided they should get an official weight on the fish, so they took it to Rathbun Fish Hatchery. Unfortunately, the hatchery’s scale wasn’t certified, but while they were there someone told them they believed the fish was a black crappie because it had seven or eight spines in the dorsal fin.

With a record-beating weight of more than 4 pounds on the unofficial scale, the duo knew they needed to take it for an official weigh in. A nearby meat market with a certified scale verified the claim: 4.08 pounds.

Foster called a Bass Pro Shops located outside of Des Moines and asked if they wanted a state-record black crappie for the store’s big fish tank, and they said yes. The pair transported the crappie, which was very much alive, to the Bass Pro and plunked it in the tank, where it remains today. A fortunate turn of events, allowing it to be tested.

HYBRID CRAPPIES

“Crappie are a prevalent hybrid species. Black crappie and white crappie spawn with each other quite a bit, where they occur together,” Schultz explains. Schultz doesn’t have any hard numbers on how often this occurs in Iowa waters, but it’s often enough that he isn’t surprised by it. Schultz also notes that hybrid crappie, bred in a hatchery, are often released into the wild.

“When it comes to these hybrid crappie, they can actually be stocked that way, too. And the reason for that is what they call ‘hybrid vigor.’ Those fish that are hybrids tend to grow faster, at least the first generation, than their parent species,” Shultz adds.

“[Because it’s a private lake], somebody could have legally purchased these fish and put them in there, too. I want to make sure that’s clear [Foster] didn’t do anything wrong, if indeed, that is the case. So we’re not sure just what route we got to this fish, but it sure is a nice one.”

We should know soon enough, when the results of the DNA testing become available.

WHAT ARE HYBRIDS?

A hybrid is the offspring created when two different species of animals mate, resulting in an individual with genetic traits from both parents. It’s something most commonly seen in captive animals, such as livestock or certain strains of hatchery-reared fish like splake (lake trout, Salvelinus namaycush bred with brook trout, Salvelinus fontinalis) or tiger muskellunge (muskellunge bred with northern pike; Esox masquinongy + lucius or Esox lucius + masquinongy).

But it does also occur in the wild, most obviously in ducks that wear a combination of the plumage of their parents, such as the so-called Brewer’s duck that is a result of a mallard and gadwall. Natural hybridization can also occur in fish. “Cutbows” are the result of rainbow breeding with cutthroat.

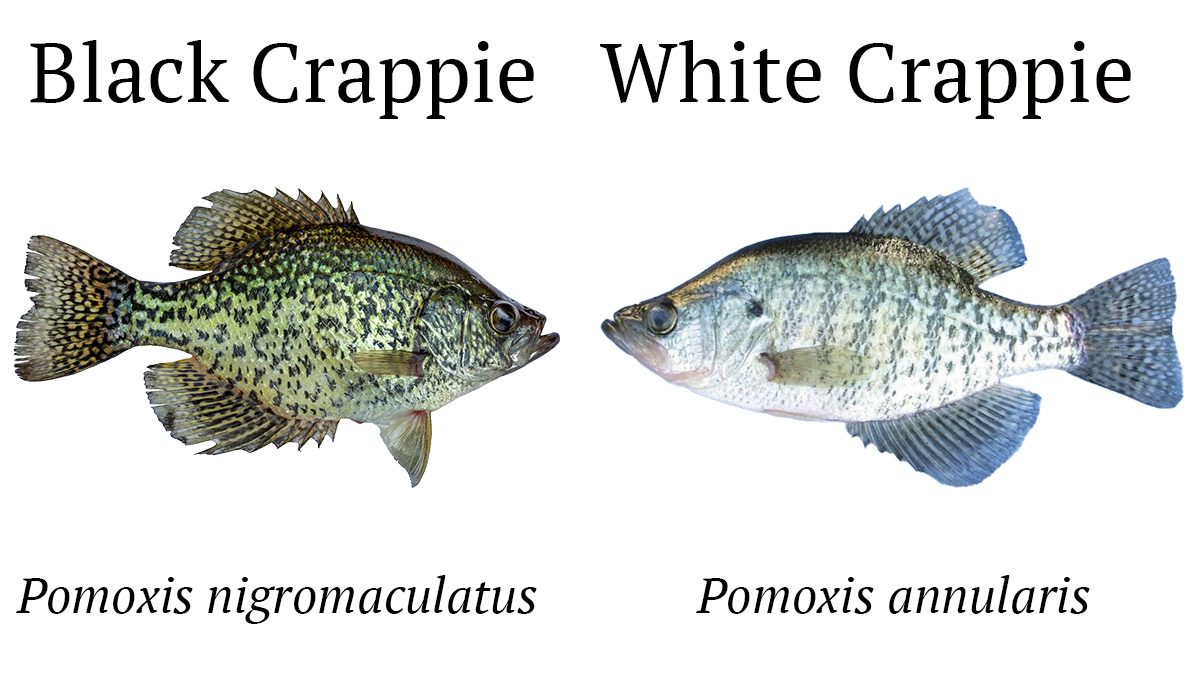

One of the more common hybrids seen in the fish world is a cross between black crappie (Pomoxis nigromaculatus) and white crappie (Pomoxis annularis). Most hybrids are sterile, but because they are the same genus, Pomoxis, these fish can produce fertile offspring.

Just how many hybrid crappie exist in the wild is anyone guess, as the rates of hybridization vary wildly. A study conducted on 10 reservoirs in Alabama from 1992 through 1995 by the Department of Fisheries and Allied Aquaculture, Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station, Auburn University found that natural hybridization between black and white crappies ranged from 0% to 21%. In one basin, hybrids accounted for less than 2% of crappies, while in other reservoirs they made up 14% to 21% of the crappie population respectively. Second generation hybrids were rare even in the more abundant populations.

A later study, Hybridization Between Black Crappie and White Crappie in Southern Illinois, conducted by the Southern Illinois University at Carbondale Fisheries Research, Illinois Aquaculture Center and Department of Zoology in 2002, aimed to quantify the phenomenon in northern waters, as most of the previous research into the subject occurred in the South and Southeast. Their results showed less prevalence, with the range of crappie hybridization rates was 0% to 7.9%.

The researchers in that study also found that because the rate of hybridization was so low, they were able to correctly identify 93.7% of the black crappie and 99.6% of the white crappie by using traditional field marks such as coloration and dorsal spine count.

But making a correct identification isn’t always that easy. White crappie typically have five or six dorsal spines and black vertical bars on the sides of the body; black crappie have seven or eight dorsal spines and small mottled black spots on the sides of the body.

However, there can be overlap in appearance that can complicate identification. A publication by the Southern Regional Aquaculture Center profiling hybrid crappies says even though there are certain identifiable characteristics between the two crappie species, genetic analysis can be needed to tell the two apart. As was the case with John Foster’s giant.