Muskellunge or Musky are one of North America’s largest sport fish. They are known for their large size and aggressive behavior toward bait; they challenge anglers at every cast. Their popularity has made them a sought-after game fish, providing a challenging catch for many anglers.

MUSKY HISTORY

Muskellunge Esox masquinongy has deep roots in Native American language and history. The Ojibwe called the fish Maashkinoozhe. The scientific name is derived in part from Latin and Native American Cree. Esox comes from the name given to the Pike family from Europe. Masquinongy combines the Cree words mashk, meaning deformed, and kinonge, which translates to pike.

Common names: Musky, muskie, muskellunge, white pike, maashkinooze, maskinonge, and barred musky

MUSKY IDENTIFICATION

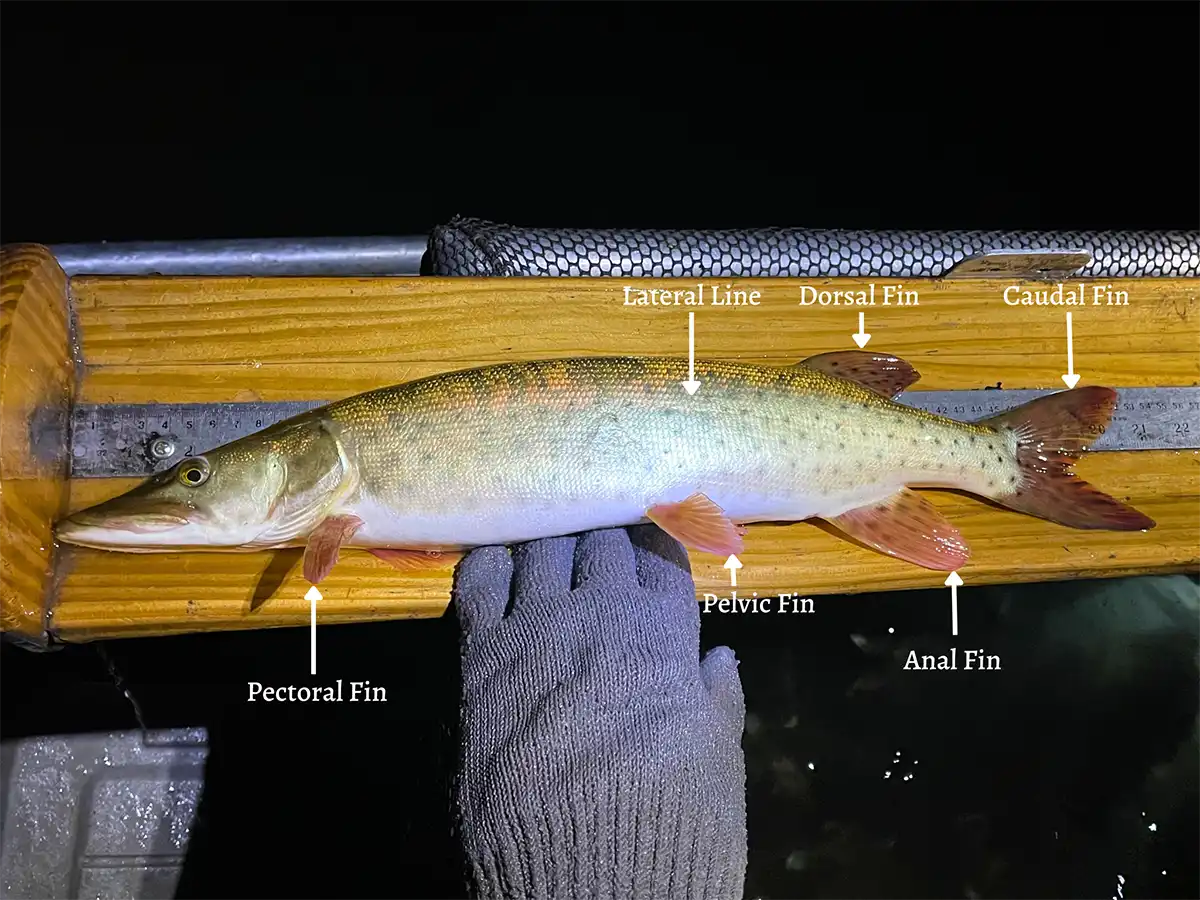

Musky are the largest fish in the Esox family. They have an elongated cylindrical body with a dark back, grayish-green side profile, and a silvery white belly. Their sides can be marked with spots, stripes, or blotches along the length of the body that fade as the fish ages. Their fins are green or reddish-brown, with dark blotches or stripes. The caudal tail is forked, with the dorsal and anal fins located immediately in front of the tail. The dorsal, anal, pectoral and pelvic fins are relatively soft with pointed edges.

While marking characteristics vary from fish to fish, three recognized geographic patterns of specific barring have been observed.

- The “clear” variation is generally found in the Wisconsin, Minnesota and Manitoba areas, with either no markings or very little barring on their sides and fins.

- The “spotted” variation in the St. Lawrence and the Great Lakes region have uniform spots or blotches along its body.

- The “barred” variation is found along the Ohio River region and has large vertical stripes, blotches along its body with more minor spots and stripes on the fins.

Musky have a large, duckbill-like snout filled with canine-style teeth on both the upper and lower jaws. Below their jaw are sensory pores that can be counted to help correctly identify them from pike and pickerel species. When the jaw is viewed from below, muskies have six or more pores along each side of the underjaw, pike have five or fewer and tiger muskies have 5 to 8. The gill membrane contains delicate bones that create branchiostegal rays, which can be counted on all Esox family members.

- Musky have 16 to 20

- Northern Pike have 13 to 16

- Chain Pickerel have 14 to 17

- Redfin Pickerel have 10 to 14

- The hybrid Tiger Musky has 12 to 20

The final significant characteristic that can help clarify the identification of a musky from the rest of the family is the presence and absence of facial scales. Musky scales should only be present on half the face; pike will have the entire face covered, and pickerel or tiger musky will have just the cheeks and gill covered with scales.

The combination of musky and northern pike creates a sterile hybrid known as the Tiger Musky that contains traits from both fish. This is now a commonly stocked sportfish variety in northern state-managed and private fisheries.

MUSKY LOCATION

Musky are only native to North America, with native populations occurring from the St. Lawrence River basin to the westernmost parts of the Great Lakes region. Their range also reaches from the southernmost parts of Canada, around Quebec and southeastern Manitoba, down through the Mississippi River basins and to the southern regions of the Appalachian mountains.

Due to introductions outside their native range, non-native populations are present from the East Coast to as far west as central Colorado. Some attempts at introducing populations further west and south have mostly failed. Evidence has shown that historic populations once inhabited the Tennessee River, inferring that some native groups lived as far south as northern Mississippi.

To visualize the range of musky, we created this interactive map.

MUSKY SPAWNING

Musky begin their spawning process between April and late May when the water temperature is between 50 to 55 degrees. A male and female will pair up and move into shallow, warm water bays to begin a spawning event that won’t last much longer than a week. Rather than nest building, the pair will cruise several hundred yards of suitable shoreline, randomly depositing their eggs over aquatic vegetation and submerged debris. The spherical, amber-colored eggs sink and settle into whatever structure they are dropped over. The female will drop eggs from 20,000 to 200,000 in water 2 to 6 feet deep. The males will occasionally violently thrash their tails to aid in scattering eggs, sometimes resulting in life-threatening injuries on the body and fins.

After dispersal, the females leave the area, and the males stay within the spawning area for a few weeks. The males do not directly protect the eggs other than their influential presence. This lack of protection from the adults results in heavy predation on the eggs and fry. Small fish, insects, and crayfish will all target musky eggs as a food source. The eggs will take around two weeks to hatch and fry based on water temperature. Adult musky will eventually return to the same spot in sequential years to repeat the process.

MUSKY SIZE AND LIFESPAN

Musky’s lifespan depends heavily on its environment. Generally speaking, males mature at five to seven years, while females take longer to develop and mature at six to eight years. As with most toothed predatory fish, musky grow quickly initially, but as they age, their growth rates slow dramatically. A growth rate beyond 10 inches a year can be typical in the first two years of life, with 3 to 4 inches of growth expected in subsequent years, slowing to almost no growth annually beyond 12 years of age. Although somewhat variable geographically, trophy musky are considered to be individuals between 45 and 50 inches in total length.

Females typically live longer than males, with an average lifespan of 12 to 18 years compared to 10 to 15 years. Older fish have been observed to live as long as 30 years.

MUSKY HABITAT

Musky are cold-water species that live in lakes, rivers, and streams. They prefer cooler temperatures ranging from 32-72 degrees; however, their optimum growth rate is around 68-75 degrees. These fish can only withstand temperatures up to 90 degrees in warmer water bodies. They prefer clear water to aid in foraging and do not adapt well to long-term turbid conditions. They are also uniquely tolerant to low dissolved oxygen levels compared to most other species in their northern environments.

Adult fish spend most of their time in shallow bays where they lie waiting and sometimes cruising for forage. Weedy aquatic vegetation is often favored in these shallow areas, where they lurk in the shadows beneath the plant canopy. The juvenile stages of musky mainly utilize deeper water and drop-offs for grouping and protection from predators, including adult musky.

In river and stream systems, musky mainly resides in deeper pooled sections where the current is slower. Their presence in river systems can be highly dependent on water flow, with pulses of fast current causing them to abandon spawning and experience high egg loss.

Musky have a defined home range that they seldom stray from other than to spawn. The size of a musky’s home range mainly depends on food availability, the size of its water body, and seasonal conditions. If food is abundant, musky can sustain themselves in a smaller area, while food scarcity will encourage more movement and a more extensive range. Consequently, the range size can change depending on the time of year. On large lakes during the warmer months, the range size is an average of 120 acres. However, the range size in cooler months can reach up to 340 acres.

MUSKY DIET

Musky are the apex predators in almost all environments. Their growth capabilities and large diet enable them to eat most fish species around them.

Fingerling-sized musky feed on plankton immediately before moving to insects.

The juvenile stage: they feed mainly on smaller fish species like minnows or shad.

Matured musky will have a diverse diet of frogs, crayfish, ducklings, snakes, small mammals, and any fish species they can consume.

During the warmer months, the musky desire for food dramatically increases, and vice versa during the cooler months. When water temperatures reach 50 degrees in the spring, musky will begin to feed more often. Feeding slows down slightly around 80 degrees during the summer and then picks up again into the fall transition. They utilize shallow, weedy areas with abundant prey to lie and wait for adequate food to pass them by. Like the northern pike, musky utilize their large caudal fin to follow prey until the optimum time to lunge forward at a high rate of speed. The many sharp teeth in the muskie’s long jaws help to grip captured fish and aid in incapacitating prey before it can be swallowed whole.

MUSKY THREATS

Musky are relatively stable in most areas where they are established. The current risk associated with muskie’s is habitat loss due to siltation and aging reservoirs. Other concerns are warming water conditions and how it will impact health at upper-temperature tolerances.

MUSKY FACTS YOU NEED TO KNOW

- The IGFA world record musky weighs 67 lbs 8 oz. It was caught by Cal Johnson July 24th 1949 in Wisconsin on Lake Court Oreilles.

- The IGFA length world record musky was 60.24 inches and was caught by Derek Balmas November 8th 2022 in New York on the St. Lawrence River

- Musky is the Wisconsin state fish