Anglers generally hold a passion for a particular species of fish and often it is tied to a specific fishery say for example the largemouth bass population on Kentucky Lake. Kentucky Lake is one of the most famous bass fishing destinations in the country, and those that live here have a special bond with the expansive fishery. That passion has led much of the tough fishing and what has happened to the largemouth bass population on the lake in the last few years to be misattributed to many different factors.

The lake is going to experience a rebound and the data is being used to not only predict but also explain what actually happens with a bass population on extensive and diverse fisheries when many ecological factors change.

This will serve as a longer narrative on what can actually hurt and help bass populations and dispel many of the common notions and conspiracy theories that really don’t affect large fisheries the way they affect smaller ponds.

Here are 8 common factors for focus that can affect or at times mistakenly get blamed for a decline in a largemouth bass populations:

- Over harvest

- Tournament pressure

- Carp influx (i.e. food competition)

- Lack of grass

- Water levels around the spawn

- Habitat

- Stocking

- Spawn Class Size and Abundance

Historical Bass Populations on Kentucky Lake

By looking at a bass population on a fishery like Kentucky Lake and the data that has been collected over the years on the fishery and the fish, by fish and wildlife agencies in Kentucky and Tennessee as well as a much broader scope of studies from around the country, we see how different factors can affect largemouth bass populations.

“The view of a lot of people is that the bass fishing was good on Kentucky Lake starting in 1948 and stayed good until the carp showed up and killed them all,” said Adam Martin, Western Fisheries Biologist for Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources, with a smile.

Of course that’s not remotely what happened, and we’ve seen equally as bad, or even worse declines in previous decades than we’ve seen during the recent downturn in fishing on Kentucky Lake. In fact, the fishing on Kentucky Lake for largemouth bass was pretty poor for decades. It was more of a crappie fishery until the 1980s when grass and clearer water became more prevalent in the river system. There were more drought periods in the 80s and grass flourished.

In other words the environmental conditions changed and bass fishing got better. But still not as good as it would get later in the 2000s.

Today bass fishing is more popular than crappie fishing on Kentucky Lake due in large part to decades of pretty good bass fishing on the lake and the popularity of the sport of bass fishing tournaments in general.

A number of factors can contribute to the rise and fall of largemouth bass populations on any given fishery. And while many people think just one thing hurts a population, it’s more likely that many things have to happen simultaneously to have a true decline. We’ll address many of those as they relate to Kentucky Lake because Martin, the KDFWR and the TWRA have shared so much data about the many factors affecting this fishery over many decades.

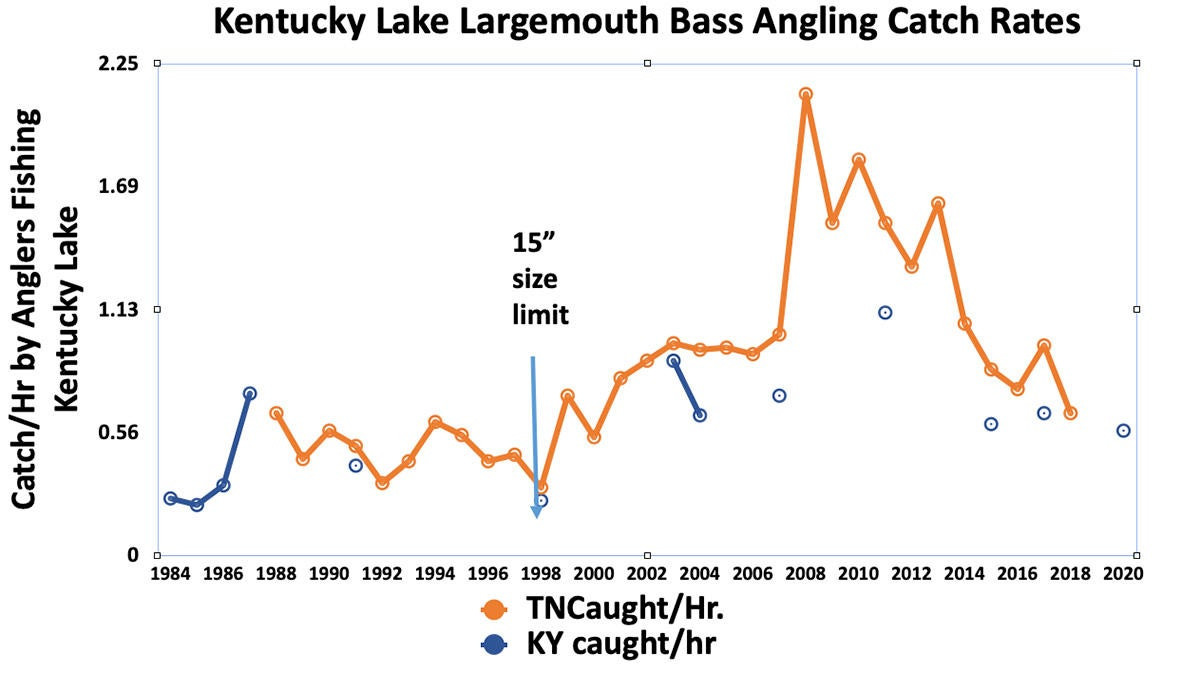

TWRA and KDFWR have been keeping detailed creel survey results and catch per hour rates over time. This is the easiest way to measure the health and trends of populations on a fishery.

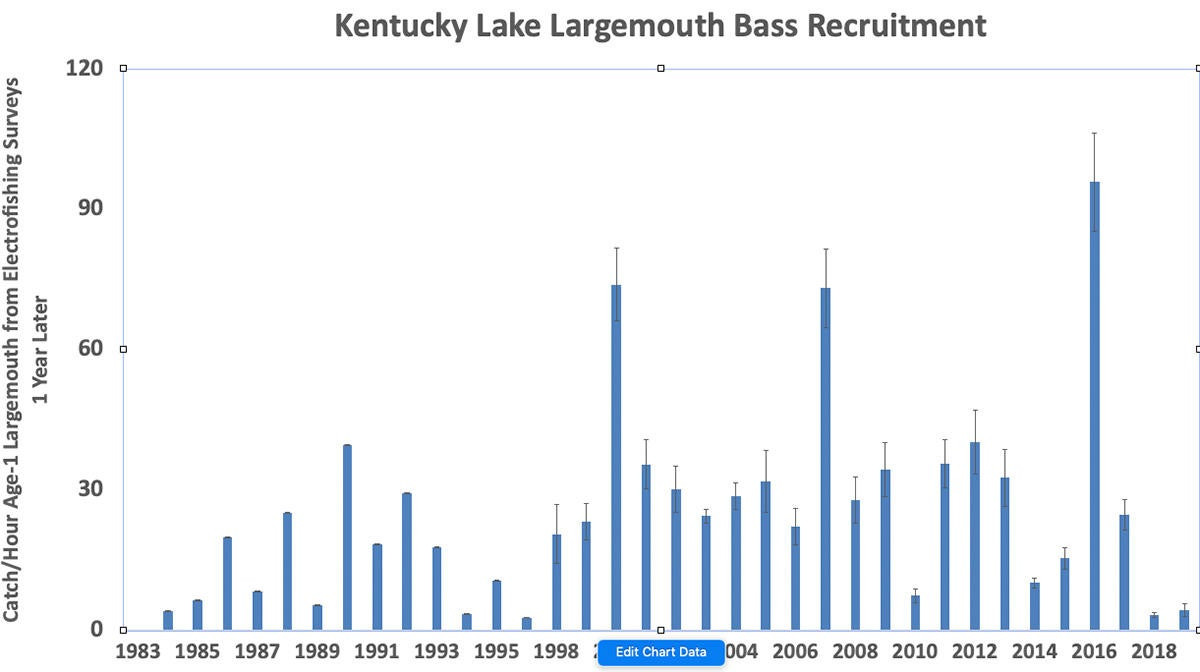

In the late 90s, there was a decline in the bass population on Kentucky Lake. Anglers and biologists were concerned about the population and the fishing and set the minimum length limit of 15 inches in 1997 in the hopes that it would slightly decrease harvest and improve the fishery. While largemouth bass virus was a concern at that time, the true culprit as studied through electrofishing surveys was three bad spawn classes in a row. And what we saw for tournament results around that time were actually as bad or worse than what we’ve seen recently with tournament results.

Then in the 2000s, the fishery saw an explosion of good bass fishing. More habitat was in the lake with grass. But the catch rates could also simply be attributed to advent of side imaging and anglers getting a lot better at finding large concentrations of bass all of the sudden. And that’s partially why the recent downturn appears so dire on the lake when in fact it’s probably not as bad as ones we’ve seen in years past according to the data. It’s more a function of it was so much better and then took a steep downturn.

And this is not a situation where anglers are confused or how to catch fish consistently has radically changed. It is in fact tougher to catch a bass than it was 5 years ago because the bass population numbers have actually declined. So we have to look at the factors that could have caused what is happening with the population now.

Is OverHarvest Hurting Bass Populations on Large Reservoirs

When fisheries start to decline, one of the first natural impulse reactions is to blame people catching and killing too many fish as a reason for the decline. In the 80s and before, people caught bass, kept them and ate them. But Catch and Release initiatives became mainstay in the late 80s and early 90s and over-harvest on Kentucky Lake became a non issue to the population.

“We’ve been cruising at about 2 percent harvest rate since the turn of the century because catch and release is so big now,” Martin said. “In the 80s, people caught bass and ate them. That’s not the case as much anymore. So we believe over-harvest is no longer an issue that affects our bass populations at Kentucky Lake. In fact, on a national scale, the reality is that for most lakes, particularly smaller lakes, underharvest is much more likely to be a problem which hurts the fishery due to overabundance and reduced growth.”

Does Tournament Pressure Hurt Bass Populations

Martin has been studying the tournament catch rates compared to overall creel surveys and knows that roughly 20 percent of the bass caught on Kentucky Lake are caught in tournaments. It varies year to year, but that’s the average. Not 20 percent of the fish but rather 20 percent of fish caught which is dramatically less than the total number of largemouth bass in the system.

From there, he teases out the percentage of fish caught in the summer. Because there is relatively low mortality in cooler months, you only really need to be concerned with summer months. So only 25% of the fish caught in tournaments (20% of all fish caught) are caught in summer events. Meaning 5% of all caught fish are caught in summer tournaments and are subject to higher mortality rates.

“Summertime tournament mortality rates vary a lot with some estimates as high as 70 percent, but for modeling purposes, I use the average mortality rate of 40 percent and apply that rate to the percentage of bass caught in summer tournaments,” Martin said. “It’s fair to estimate that only 2 percent of the bass caught in Kentucky Lake each year die during tournaments.”

Even if you were to ban tournaments at a huge socioeconomic cost, you’re at best saving 2% of all bass caught with almost no effect on the other 98%. So this is negligible to the population as well. That’s not to say this won’t happen on smaller bodies of water. But it’s just not affecting the population on Kentucky Lake to a large enough scale to be the cause of decline.

Can Invasive Species like Asian Carp Ruin the Population

The influx of Asian carp has certainly affected the fishery, and every effort needs to be made to remove them from the system. Millions of federal dollars have been allocated to their removal, and this will definitely help the fishery as a whole rebound better.

But the carp influx is complex in its effects.

“Many state agencies including mine will have some form of the sentence: ‘Asian carp can outcompete our native species because they feed on plankton and all larval fish feed on plankton’ on their website. Which is true in a very broad sense, but the actual effects of Asian carp will be different for each species and for each life stage of fish with some life stages even experiencing positive benefits.”

There is potential diet overlap not only between carp and bass fry, but also with carp and other forage species. That is the real issue that should concern anglers.

“You need two things for diet competition,” Martin said. “First you need diet overlap, or feeding on the same resource in the same place at the same time. Secondly you need a limiting food resource, or basically, there is not enough food to go around.”

So silver carp, the dominant invasive carp in Kentucky Lake, feed on phytoplankton and zooplankton. Small bass just after hatching feed on zooplankton. So for that small window there is potential for direct competition on diet, but whether competition is actually occurring in Kentucky Lake is far from certain because we don’t know for sure that there isn’t enough zooplankton to go around at that time of year.

Native shad species like threadfin and gizzard feed on phytoplankton and zooplankton as well, so again, there is potential for overlap. Which potentially can cause slower growth for bass who rely on shad as one of their primary food sources.

Murray State University and Hancock Biological Field Station have been studying plankton levels in Kentucky Lake since 1988. Their reservoir research team have more information about carp effects on the fishery than most. Dr. Michael Flinn (MSU) has shown that chlorophyll levels (a proxy for plankton levels) potentially declined after 2010 and 2015 when the carp spawns hit the lake, but that it has not had a long lasting effect on plankton levels.

While carp could certainly disrupt fish that are spawning and hatching and needing zooplankton in the spring as the silver carp are filter feeding 24/7, to see if that is affecting juvenile bass abundance, you have to look at them at different stages of the year.

“We have been collecting juvenile bass since 1985 through electrofishing,” Martin said. “We collect them first in October, their first fall as age 0 fish. Then again the following April or May, we collect them as Age 1. So what we might expect that if the carp were having a negative impact, the average size of our young bass would have been good until a large carp spawn and then it would have dropped off. However that is not what we saw. Pre-carp and post-carp we still see lots of ups and downs and wild swings in the average lengths of age 0 bass each October.

“The results of our bass growth studies have been a bit unexpected, because I expected to find that a lack of food during that critical first summer was the reason for our poor bass spawns. Some prior work at Kentucky Lake showed that the overwinter survival is pretty low for bass that are less than 5 inches in that first fall. So if silver carp were reducing the average size of our age-0 bass through diet competition it would perfectly explain why we have seen some poor year classes in recent years.

“To test that theory we basically looked at the size of young bass each year and compared it with the abundance of young bass. The theory being that in years with a good spawn and a lot of young bass in the fall, an overall lack of food should cause them to be shorter than in years with a low abundance of bass. The relationship we would expect if carp are affecting bass growth rates, then the age 0 bass in the fall should be shorter. So if food is limiting, they should be smaller if there is more of them and longer if there is less of them. We see the opposite when we look at the time period of the carp invasion from 2004-2018.”

“So our years with the largest catch rates also have the longest average lengths in the fall. That was surprising to us as biologists. Three of the four top year classes as far as abundance were also the best years for average lengths. So not only did we not see the negative relationship between abundance and growth, we are seeing the opposite. It can’t be that because there are more fish they are longer. So it’s likely caused by another factor. At least for the moment, we don’t have much evidence that Asian carp are limiting the food resources for our young bass, at least not yet.

“We have also not seen a decline in the growth rates of our adult bass, and outside of one year – in 2017 – the fish are in really good condition showing healthy length to weight ratios.

“So it isn’t really obvious to me that carp have hurt the population of bass. Kentucky Lake was booming after the 2010 carp spawn. It was already cycling down in the 2015 spawn from other factors like spring climate patterns and the effects wet vs. dry springs; it just wasn’t showing up yet in the fishing.

“This is great news for Kentucky Lake bass anglers, but it’s important to keep in mind that Asian carp are still a huge problem and other fisheries are likely to experience harsher impacts if they continue their population expansion.”

Does the disappearance of grass mess up the population

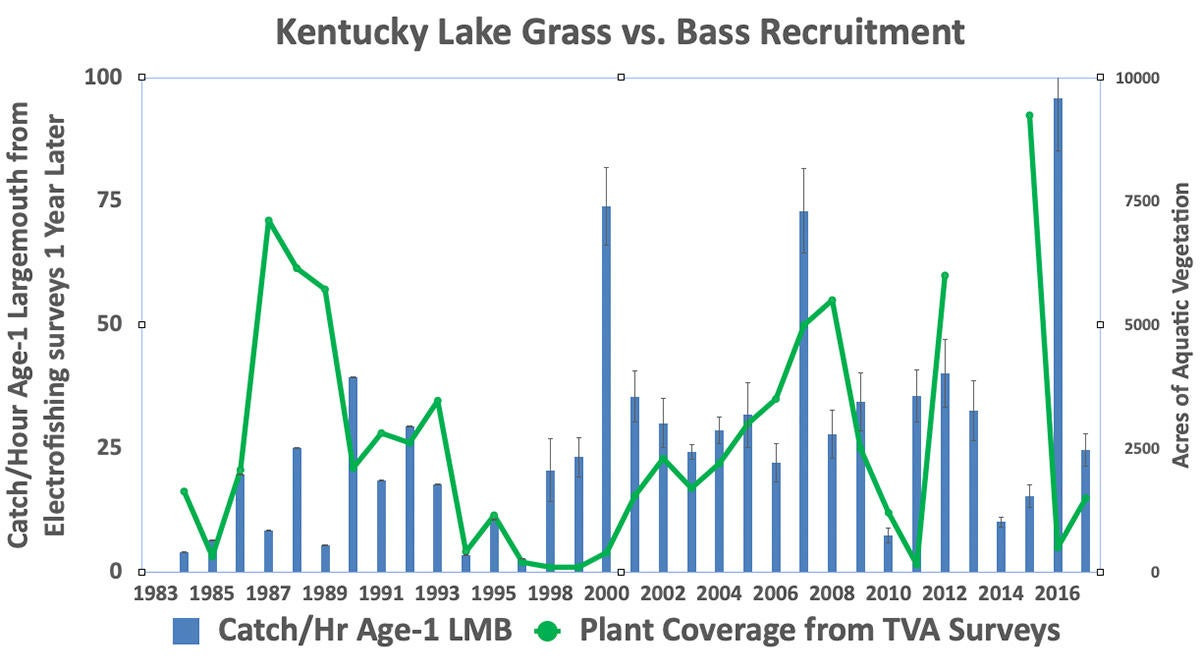

Many anglers equated the grass disappearing in 2015 with the subsequent decline in bass fishing that followed after. So it makes a clear association for people, but it’s also not the cause. Grass has an effect on fishing quality for sure. But not as much as we may think on spawn recruitment, or the success of spawning year classes.

“TVA biologists monitor the levels of vegetation in their reservoirs,” Martin said. “They does flyovers every year, and we have a lot of data on surface acres of grass on Kentucky Lake going back decades. You would think that grass would improve the survival of juvenile fish enough to impact the spawn in a positive way. That thinking would then say we could use the amount of the grass coverage in a lake to predict the success of the spawns.

“But the data doesn’t show that. When you plot them together, you see that some of highest years for grass coverage were some of our lowest spawns and some of our lowest grass coverage years are some of our best spawns. So that is not a predictor of spawn class success. There is no real relationship there.

“It makes fishing more fun, but those main lake grass beds don’t seem to improve the spawn on Kentucky Lake. Also, when it’s a good spawn on Kentucky, it’s almost always also a good spawn on Barkley. And, Barkley has almost never had grass. In some lakes, the amount of aquatic vegetation can be hugely important, but at Kentucky and Barkley, it’s harder to make that case.”

What about water levels around the optimal spawn water temperatures

Martin has been studying the spawn temperature range that is the most important to predicting bass populations and his conclusions may ultimately help with population successes. This next part is the most fascinating thus far in understanding how to keep populations successful in a perfect world.

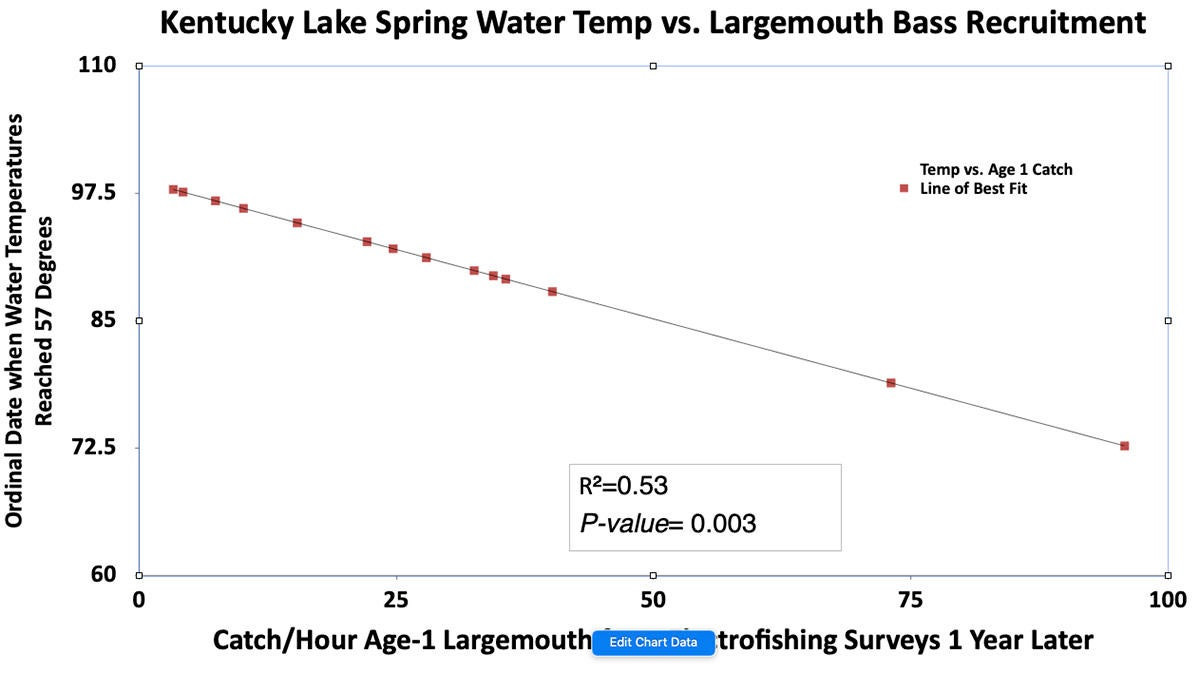

“The most important time on Kentucky Lake in terms of largemouth bass population is when the water temperature ranges from 57 to 65 degrees,” Martin said. “And you can actually predict the success of the bass spawn on Kentucky Lake if you know the number of the days that the water temps will be in that range as calculated by your catch rate of age 1 bass the following spring.

“Water temp sensors were installed by Murray State University and Hancock Biological Station in 2005. In general, when you have a high number of days of 57 to 65-degree water temps in the spring, you usually have a high number of bass spawned. If you have a low number of days between 57 and 65 degrees, you have a low number of bass spawned. In some years, we have 35 days in that temp window, and it’s a great spawn. In some years, we have 15 days in that temperature window, and we have a bad spawn.”

While bass will spawn as water temperatures climb into the 70s, Martin has found that the data is not as reliable when the range is wider. So the number of days in that early spawn temperature range is the best predictor.

“We did snorkel studies where we watched bass, bluegill, redear and longear sunfish throughout the spawn,” Martin said. “The bass get there first, then the bluegill, then the redear and then the longear sunfish. Most of it is based on light period and water temperature. So if you have a period where it goes from 50 degrees to 80 degrees quickly, you’re going to have more overlap and a shortened spawning window for each species. In ideal circumstances, you have bass show up the last week of March, and bluegill show up the first week of May.

“That longer temperature window in the early period creates more time for bass to spawn. Additionally, it’s also important when it comes to growth. Theoretically the timing affects how long the fish will grow to be in the fall. An earlier-hatched fish will be longer in the fall because it had more time to grow. A longer temperature window for the bass spawn also has the effect of delaying the bluegill spawn. That delayed bluegill spawn can also be a good thing because it gives the young bass more time to grow big enough to eat the newly hatched bluegill fry. We can basically explain young bass abundance and predict their fall lengths just by knowing the date when the water temp first gets into the range.”

“When the lake reaches 57 degrees on day 100 of the year, the fish are likely to be smaller in the fall. But if it reaches 57 degrees on day 70 of the year, the fish are likely to be much larger in the fall. The date when it reaches 57 degrees is also a good predictor of the age-1 catch rates the following spring.”

For a healthy population of bass you want newly hatched bass to be as large as possible that first fall so that they can switch to eating shad and a larger buffet of food options for growing at a much faster rate. This can be the difference between making it through the winter or not because a lot of anglers forget that a huge portion of the bass that are spawned don’t make it through the first year.

Now knowing how important this temperature range is and maximizing the number of days fish spawn in the early period is of maximum importance. With Kentucky Lake, that temperature range often starts in March or April when the lakes are not at full pool. So the habitat requirements for a successful spawn are degraded. While much of the KDFWR habitat effort has been in placing cover in the lake to improve fishing over the years, the last few years, biologists have been focusing on cover that affects more successful natural spawning in the early low water periods on Kentucky and Barkley.

Martin, and his TWRA counterpart Michael Clark, have also worked with U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and TVA on not rapidly dropping our water levels if we are in that prime spawn temperature window. The TVA and Corps of Engineers have been very open to Martin’s recommendations as their biologists tell them the same things about dramatic effects on the spawn, but in massive flood stages, the Corps will take over management for the more important Flood Control Plans where you are talking about people’s lives, homes and land.

“The idea that TVA and the Corps don’t care about fish is completely untrue, but it is true that they will prioritize flood control over fishing,” Martin said.

Spawning Habitat

Martin believes habitat is the thing we can impact the most at relatively low cost to provide for better spawns and better bass populations. Although he readily admits habitat can’t be tested effectively to know for sure if it’s the largest contributing factor on spawns.

So the question is what is ideal for improving spawning success with habitat?

“A study done in Arkansas showed that fish prefer to spawn in less than 10 feet of water, on fine or coarse gravel, usually near simple structure like a laydown or a stump,” Martin said. “They don’t like spawning structure that is too complex because it will be attractive to nest predators. Usually 30 feet apart is best, so there is not as much fighting between the males.

“In most lakes, the idea that spawning space is limited is crazy. This is particularly true for smaller and shallower lakes where the entire shoreline is good spawning habitat. However, in Kentucky Lake, if you really look at the ratio of good spawning areas to total acreage, the idea that spawning space may be limited starts to sound less crazy.

“Kentucky Lake had an abundance of button bushes. Erosion and floods have left button bushes confined to 358 feet above sea level or higher elevations with summer pool being 359. So there is just not much cover until the lake is at summer pool. There is a lot of open shoreline and few button bushes in the very back. It doesn’t get good for habitat until 359.”

“That’s an issue for Kentucky Lake. In a typical year, the button bushes and the best cover don’t get flooded until about 64 degrees. So that’s not ideal because we want them to be able to spawn earlier. So we have been purposefully adding habitat designed for bass spawning at lower elevations so that it’s available in that pre-summer pool period. We’re putting in cypress trees, spawning benches, and artificial beds on both lakes.

What all this should do is spread fish out and provide more fish spawning opportunities regardless of water level. Theoretically, it may even encourage more bass to spawn earlier in the year.

Kentucky Lake and Lake Barkley are massive fisheries and the local Kentucky Fish and Wildlife district’s habitat materials budget is small ($3,500 for both lakes in 2020), but a cooperative grant with the Corps of Engineers to which Wired2fish is a partner of, is providing $30,000 of funding to put a lot of cover into Lake Barkley to increase spawns and bass recruitment. TWRA is doing a large part of the work as well. More than 1,000 cypress trees, 320 shallow water attractors, 1,200 laydowns and 450 artificial spawning beds will be added in just the first year.

The funding is provided by the Reservoir Fisheries Habitat Partnership, which is a federal program designed to increase funding for fish habitat while bringing together different government agencies and concerned groups like fishing clubs and small businesses. Additional partners include local hardware stores like Akridge Farm Supply, as well as the U. S. Forest Service, the Kentucky BASS Nation, the Kentucky Bassmasters club, the McCracken County High School Bass Fishing Team, and the Murray State Bass Anglers college team.

Why Don’t We Just Stock More Bass

Stocking is done to increase abundance or alter the genetics in a population. Martin has studied the stocking results of 75 bass stocking attempts across the US, including a review by Dr. Steve Lochmann of the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff that looked at 41 scientific studies where they attempted to stock bass.

“In these 75 attempts, the biologists actually calculated the age 1 contribution results,” Martin said. “Basically before they stock, they will mark them with a fin clip or some other method which allows to be distinguishable from wild fish, and then come back the following spring and sample and determine what percentage is a result of stocking. Contribution is the percentage of stocked fish in a population.”

“At first glance the idea of adding more small bass to solve the problem of low numbers of small bass seems like the most linear and straightforward solution of all, but when you really start looking at other lakes where they’ve tried this, the plan starts to fall apart.”

“The average stocking rate from those 75 attempts was 32 bass per acre. When they came back and sampled a year later, the stocked fish made up a little less than 20 percent of the year class, or roughly one in five fish from that year class was a stocked fish. You can’t just stock hundreds of bass per acre and expect your numbers to be higher. Some of these examples, they were stocking well over 100 bass an acre but were still getting less than 20 percent contribution.

“If you look at the examples where they had more than 20 percent contribution, they were almost all on tiny bodies of water. So stocking a pond to improve bass numbers works. Stocking a large reservoir is a very different story which is why it’s rarely attempted. The largest lake studied was 21,000 acres (compared to 218,000 acres for Kentucky Lake and Lake Barkley), and its contribution rate was very low at 5 percent.”

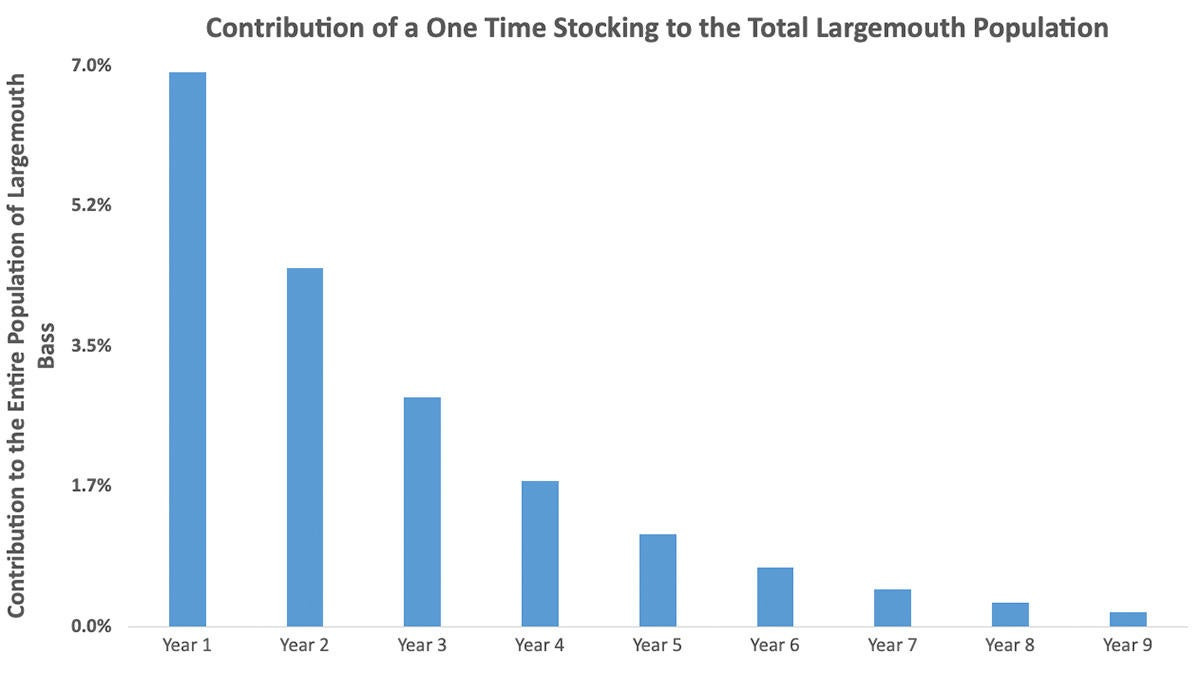

“To match the average stocking rate from those studies, you would need to stock around 7 million bass in these lakes every year to maybe get that 20 percent contribution to the fishery. You can’t just stock one year because you would only contribute to one year class. A bass might live to be 15 years old in Kentucky Lake, so at any given time you have about 15 year classes in the system. If for example you stocked bass in only 2021 and the stocked fish somehow actually achieved the average year class contribution rate of 20 percent to the 2021 year class as we saw in those smaller lakes, it would still only be 6.9 percent of the total population.

“By the time those hatchery fish reached 5 years old (average age to reach keeper size in Kentucky Lake), they would only make up 1.2 percent of the total population. So it would have to be done annually for 15 years in a row to potentially achieve that 20 percent contribution to the entire population of bass.

“Those 7 million bass are more than all our state hatcheries could produce in a year even if we halted production of all the other species of fish. You could stock that many fry, but stocking fry is close to useless in most water bodies because most won’t make it. To raise advanced sized fingerlings is expensive and may cost anywhere between 75 cents to a dollar per fish.

“So to potentially see a 20 percent increase in our bass numbers with stocking we would pay somewhere between 75 and 105 million dollars, knowing the majority aren’t going to make it and contribute. That kind of money certainly isn’t available in state fisheries budgets, but even if it were, it still wouldn’t be a home run idea to spend it trying to stock a lake this size. It’s not that stocking would have no benefits, but rather it’s simply that the benefits would be very small and the costs are astronomical compared to other management options.”

Not to mention you can alter the genetics, like what happens when you introduce Florida strains. And those genetic alterations are irreversible. So fish that are maybe more difficult to catch in colder weather get a small foothold and the perception will be that fishing is tougher. We’ll save the Florida strain stocking explanation for a separate article, but studies have shown it’s not going to make a huge reservoir a trophy destination in a decade as far north as the Kentucky end of Kentucky Lake.

What Actually Happened to the Bass Population in Kentucky Lake

Kentucky Lake had poor spawns in 2014 and 2015, likely due to delayed but rapid warm up trends those springs. This is very similar to what happened in the late 90s. The 2016 year class was one of the best spawns as they saw a huge spike in Age 1 bass in 2017. It takes roughly 5 years for a bass to get to keeper size on Kentucky Lake, so those bass will be keepers this year. In 2018 and 2019, we had another couple of good spawns and the early signs are pointing to a great spawn in 2020. So we’re setting up to replenish our populations for another boom in bass fishing. The baitfish populations are very strong in the system currently as well meaning food abundance is good and with competition apparently low.

These are extremely large and dynamic reservoirs. Martin and other biologists have seen for years when we have a bad crappie spawn we have a good bass spawn and vice versa. It’s why these lakes can sustain good fishing for both species unlike most other lakes in the country. But the ecology of the lake continues to change now with factors like carp and clearing water.

Kentucky Lake saw spotted bass and sauger populations disappear and red ear populations gain a foothold because the ecology of the lake changed. Smallmouth are coming on stronger as the lakes clear more every year.

“Change is constant at these lakes, and if you’re locked in on only one species, I can guarantee you that you won’t have a good year every year,” Martin said.

As anglers we want it to always be good fishing but population and fishing cycles are found in every body of water in the country and have been found on this lake for decades before there ever was a zebra mussel or an Asian carp. The lakes flourished without stocking programs, more fish were harvested in decades past than now as catch and release is a constant. Tournaments don’t affect a large enough part of the population to be detrimental.

So it all boils back down to spawning year classes. If you want your populations to flourish, you need consistent year classes, or simply put, more bass to survive that first winter. Anglers and biologists have more data and tools now to follow and potentially improve spawns.

Working with agencies like the TVA to hold water for a few more days where reasonable during the spawn may pay huge dividends on our future fishing. The fact that massive complex organizations are working together for the betterment of fishing on one of the largest, most complex reservoirs in the nation should come as a welcome relief to those of us that love largemouth bass fishing and want to see it flourish for decades.