You may know there are two species of crappie, the black crappie Pomoxis nigromaculatus and the white crappie Pomoxis annularis. Many anglers commonly confuse the two and misidentify their catch. In this guide, we are going to give you the tried-and-true quick identification method for both species and additional insight into everything you need to know about crappie and crappie fishing.

CRAPPIE HISTORY

Crappie belong to the sunfish family (Centrarchidae) which also includes bluegill sunfish, smallmouth bass and largemouth bass. The two crappie species are the only members of the genus Pomoxis worldwide.

A white crappie from the Ohio River was the first to be formally described by Turkish naturalist Constantine Samuel Rafinesque in 1818. He gave them the name Pomoxis annularis. The Latin name annularis has a meaning of “relating to or having rings”, referring to the vertical patterns found on the sides of the white crappie.

A black crappie from the Wabash river was first described by French naturalist Charles Alexander Lesueur in 1829. He gave them the scientific names Cantharus nigromaculatus but it was not accepted instead, Pomoxis nigromaculatus was accepted and remains today. The Latin name nigromaculatus is a combination of words that mean “black-spotted”.

Crappie have several common names that include papermouths, calico bass, moonfish, white perch, speck, speckled bass, speckled perch and Sac-a-lait for those in the south. Crappie are very tasty fish ranking in many anglers’ top 3 as one of the most palatable freshwater fishes. Because of this, they are known as a “Pan” fish and large crappie is often referred to as a “slab”.

CRAPPIE IDENTIFICATION

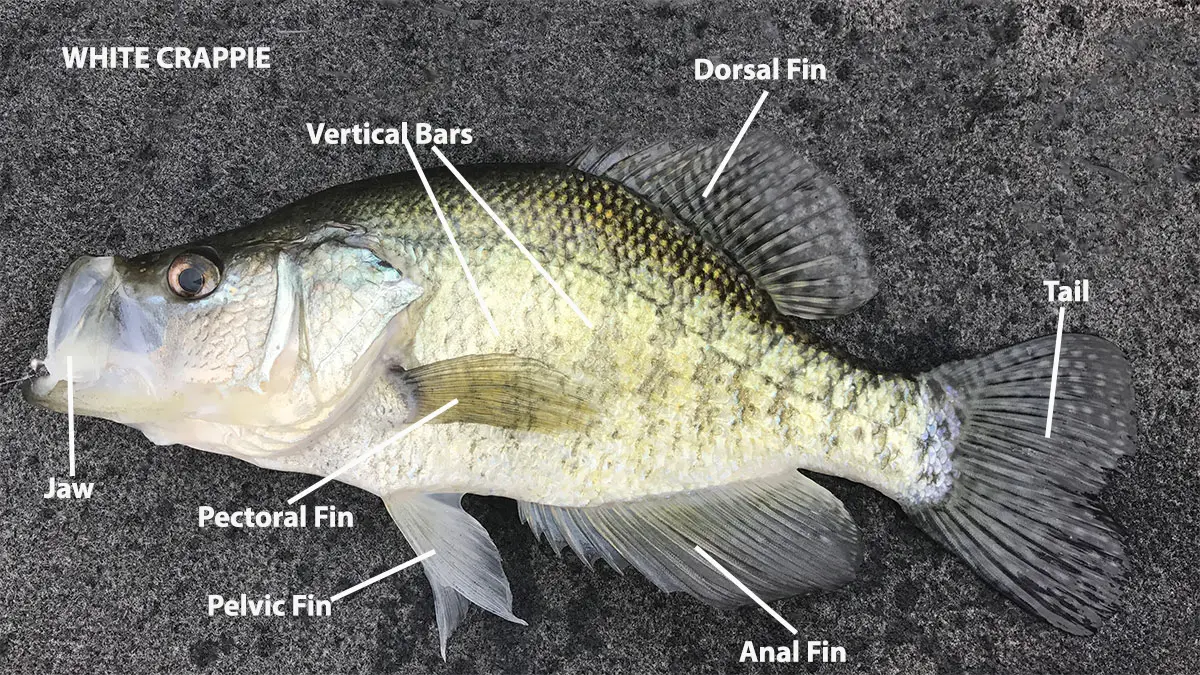

Crappie can be identified from other fish by their deep body that is laterally compressed to give a round plate-like appearance. Their sides have a dark green to olive back coloration that lightens down the body to a silvery yellow-white color on the stomach. They have a small head relative to their body size and a large mouth where the upper jaw reaches past the middle of the eye when the mouth is closed.

The center of the eye can appear to have a single black band from top to bottom. The hard and soft dorsal fins will be connected, appearing to increase in size towards the rear of the fish and end in a rounded soft edge. The anal fin will have a similar look to the dorsal fin. Dorsal and anal fin hard spines will range from five to eight depending on the species. Fin and tail coloration can appear dark with light spotting or modeling throughout.

The black crappie can be identified most accurately by counting the hard spines on both the dorsal and anal fins, there will be seven to eight on the dorsal and six to eight on the anal fin. You can also count 17-19 anal soft fin rays and 15-16 dorsal soft fin rays for better identification. Irregular dark blotches and speckles can cover the body but may not be visible depending on the time of year, water color, clarity or depth that the fish comes from. Breeding males will typically have extremely dark coloration with the head and breast nearly black.

The white crappie can also best be identified by counting the hard spines on the dorsal and anal fins. There will be five to six on the dorsal and five to seven on the anal fin. The sides of the fish will showcase the dark blotches forming 5-10 vertical bars, widening near the top of the fish. These bars can be difficult to see if a fish is caught in deep, darker or turbid waters. The color change is the primary reason hard spine counts should always be used to identify species of crappie, even for seasoned anglers and scientists.

Hybrid variations of the crappie do occur naturally with wide variations in traits that may require a genetic analysis to accurately identify hybrid crappie. There are several hybrid crappie and genetic variations in crappie. That article will go into more details of the different kinds of variations outside of the most common black and white crappie.

CRAPPIE LOCATION

Both species of crappie historically were found only within North America and more specifically in the United States. They were most prominent in the watershed of the Mississippi river and extending almost to the Atlantic coast. The black crappie native range was larger, covering the great plains east of the Rocky Mountains throughout the central regions of the U.S. and spanning most of the southern Atlantic coast.

On its western boundary, it reached from Texas to Canada and on the east coast from regions New York to Florida. The white crappie native range was like that of the black crappie but covers a slightly smaller area. Extending throughout the Mississippi and Ohio river drainage without going as far as the east coast or down into Florida.

Both species of crappie have been widely introduced throughout the United States and Mexico. Today their range covers southern parts of Canada, the entire Great Lakes region, rivers and reservoirs throughout the lower 48 states and the majority of Mexico. In introduced areas, crappie are considered native transplant species that are highly desirable to anglers looking for both sportfish and harvestable fish for consumption.

Some of the top crappie anglers in the world helped us come up with a list of the top crappie fishing destinations in America.

You can see both the historic and current range within the Wired2Fish Crappie Distribution interactive map located below. You can click on the interactive map to further explore their original and current distributions.

CRAPPIE SPAWNING

Crappie spawning in general is similar between both species, with only subtle differences that help to prevent hybridization. The spawning process for crappie begins with males moving to shallow water ranging from less than one to five feet in depth. Typically, a community spawning site is selected near overhanging brush, brush piles, timber or rock structure.

Individual male crappie build a round nest by fanning soft sediment away to expose sand, gravel and hard substrate. Nest building in a somewhat community area allows for group protection of the entire spawning site but individual protection of their own nest.

The spawning process begins for black crappie as waters increase in temperature beyond 56 degrees and start slightly later in the low 60-degree range for white crappie. As water temperatures continue to rise, females move into the nesting area spawning with multiple males over several days.

A female black crappie can produce up to 180,000 eggs while a female white crappie can have as many as 325,000 eggs. Each female will lay eggs dozens of times throughout the spawning season with up to 50 spawning sessions occurring. Eggs are adhesive sticking to sediment, rock or vegetation. They become hardened by the water over time hatching in two to four days depending on the water temperature. During this time, the male will guard his nest while the female will move onto another nest to continue to spawn with other males. Once females have committed to spawning, if water temperatures rapidly drop during a cold front, they may abandon spawning for the remainder of the year, resulting in missing year classes.

Larval fish will remain in their nest for two to six days depending on temperature. The males will continue to guard the fry until they can swim and feed independently. Once fry move out of the nest males may attempt to spawn with additional females. As the spawning season ends, black crappie will remain in shallow water into early summer, while white crappie tend to move to deep water more quickly. Sexual differences in coloration between male and female crappie will become nonexistent outside of the spawning season resulting in no external differences between sexes for the majority of the year.

Hybridization can occur especially in environments with limited reproductive habitat, low-density crappie populations, or small surface areas. Hybridization results in an F1 individual that has limited reproductive potential, therefore F2 generations are rare. F1 populations can make up a small fraction of the total population or be as high as 50% in some environments.

CRAPPIE SIZE AND LIFESPAN

The largest crappie ever caught were a 5-pound, 7-ounce black crappie caught in 2018 in Tennessee and a 5-pound, 3-ounce white crappie caught in 1957 in Mississippi. Chasing world record crappie or even state record crappie can still be done today. You need to choose the best crappie baits, the best crappie rods and be in the right locations at the best fishing times.

Crappie fry hatch at a total length of .1-inch for white crappie and .09-inch for black crappie. They absorb their yolk sac over the first two to six days following hatching depending on water temperature, by this time they double in size and will be .2 inches in length. Below this size, the two species are fairly indistinguishable, but as they increase in size spiny fins develop allowing identification. Once they can swim, crappie fry immediately leave the nest and attempt to move to vegetation or other dense habitat areas. At this time, they are primarily planktivorous feeding on small zooplankton, they continue to live within dense habitat areas feeding on zooplankton until they reach a total length of 2 inches.

Fry black crappie will begin to develop scales at .7 inches in total length and will be completely covered in scales by 1.2 inches in length, white crappie begin to develop scales at around .6 inches and will completely be scaled by 1.1 inches in total length.

In southern states, black crappie will average around 5 inches of growth in their first year, another 3 inches in their second year and 2 inches in their third and fourth year. Beyond that, growth is slow and highly dependent on forage. For white crappie in the southern states, first-year growth will be around 4.5 inches, their second and third year will each be around 2 inches of growth and subsequent years should be around 1 inch of growth.

Due to these slow growth rates, you should expect a 10-inch black crappie to have a minimum age of 3 to 4 years and a white crappie to be 4 to 5 years. In northern latitudes, their growth rate slows considerably. Growth for white crappie is maximized at a water temperature of around 74 degrees and 82 to 86 degrees for black crappie. Crappie mature in the southern U.S. at 1 year and in the northern US at year 2 or 3. Their slow growth means fish around 6 to 7 inches in length can be mature adults which leads to overpopulation and stunting in some fisheries. Crappie can live 8 to 10 years but are one of the most harvested game fish in the US leading to a shorter observed life span in most fisheries.

CRAPPIE HABITAT

Crappie are found in freshwater systems throughout most of the United States including lakes, ponds, sloughs, backwater pools and slow-moving streams. Both the black and white crappie prefer waters with little to no current. Crappie are schooling fish and will swim out to deep-water standing structure together and remain around the structure as a school. Standing rock piles, artificial reefs and brush piles are certainly preferred habitats for crappie.

The black crappie favors warmer temperate waters that are dense with aquatic vegetative cover. Their fin and tail length indicate that they have a slight advantage in aquatic vegetation compared to white crappie. Black crappie also prefers clearer waters with steep gradient structure when available. This allows the fish to go shallow for spawning and feeding opportunities with the ability to move throughout the water column to limit predation.

The white crappie appears to tolerate higher turbidity waters compared to the black crappie but will have a maximum growth rate found in clearer water. Their fin and tail length indicate that they have a slight advantage over black crappie in open water.

Crappie are environmental generalists and can adapt to most freshwater water quality. They do best with neutral to basic pH, ranging from 6.5-8.5. White crappie upper thermal limits are around 90.5 degrees while black crappie upper limit is 95 degrees. They can survive in waters with oxygen levels as low as 3 ppm and slight salinity.

CRAPPIE DIET

Both young black and white crappie will primarily feed on a combination of insect larvae, microcrustaceans, and zooplankton. As they grow in size after the first year and into the second year, they can begin consuming larger prey items such as larger insects, small fish, and larger crustaceans. For the adult black crappie, their diet will tend to stay on the smaller side favoring insects, crustaceans and small fish such as fat head and shiner minnows or small shad. Although the black crappie feed during the day, they are considered to be fairly nocturnal, being most active during the evening into the early morning.

The white crappie has slightly more active feeding habitats compared to the black crappie. The young white crappie will primarily consume micro-crustaceans and zooplankton until about year two when they begin to consume smaller fish and insects. Adult fish will consume forage items such as fathead minnows, both threadfin and gizzard shad and even small carp, bluegill, bass and crappie. Diets can and will vary greatly based on their geographic location, water conditions, forage base and overall what is available for the crappie to consume.

CRAPPIE THREATS

Crappie are a difficult-to-manage species that challenge fisheries managers with missing year classes, stunted induvial size, high harvest desirability and slow growth rates. Harvest manipulation, population surveying and habitat improvements are the primary tools used by fisheries managers as fingerling stocking is rarely needed.

Crappie, although considered to be sport fish, have extremely slow growth rates and schooling behavior that lends themselves to being forage of other larger predatory fish. They have been found in the stomach contents of many common predators such as largemouth bass, pike, hybrid striped bass and other crappie. Their high reproductive ability and early maturation do provide population stability so predatory fish rarely lead to meaningful management implications.

WHAT ABOUT BLACK-NOSE OR BLACK-STRIPED CRAPPIE?

The black nose or black-striped crappie is a normal black crappie, it just has a fairly common recessive trait that results in a thick black line appearing on the center of the bottom jay and extending down the length of the head and back of the fish. The first one was reported in 1984 in Beaver Lake Arkansas and is now common throughout the range of black crappie. They eat, grow, spawn and live just like any other black crappie.

Black-striped crappie are now sold from private fish hatcheries as both pure species as well as hybrids with white crappie resulting in an almost sterile individual carrying a slightly fainter black stripe. Their prevalence in wild and stocked populations does appear to be increasing and has now been reported in over a dozen states.

CRAPPIE FACTS YOU NEED TO KNOW

- The world-record white crappie as recognized by IGFA is 5 pounds, 3 ounces and 21 inches long caught by angler Fred Bright in Mississippi.

- The world-record black crappie was caught in Tennessee on Richesion Pond by angler Lionel Ferguson. As certified by the IGFA, it weighed an astonishing 5 pounds, 7 ounces and 19 1/4 inches in length.

- Periodically we see Golden Crappie which is a fish with a genetic condition called xanthochromism which gives the entire fish a yellow to orange coloration.

- The oldest-known age for a crappie is 15-year-old black crappie.

- The white crappie is the state freshwater fish of Louisiana.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Steven Bardin obtained his bachelor’s degree in Freshwater Biology from Tarleton State University in 2009 and his master’s degree in Fisheries Science from Texas A&M in 2013. While at Tarleton, Bardin worked for Harrell Arms at Arms Fish Farm and Bait Company. In 2011 he founded Texas Pro Lake Management. He strives every day to take a scientific approach to helping his clients maximize the production of their fisheries.

Outside of TPLM Bardin has written for Wired2Fish, taught as an adjunct professor for Tarleton State University, and served as an instructor and camp coordinator for Bass Brigade youth leadership camp. In 2021, Bardin helped Major League Fishing found their Fisheries Management Division and leads their conservation efforts today.

Bardin is a member of Texas Aquatic Plant Management Society, Texas Chapter of American Fisheries Society, Southern Division of American Fisheries Society, Society of Lake Management Professionals, Texas Freshwater Fishing Hall of Fame Board, Texas Brigades Board, Texas Freshwater Fisheries Advisory Committee and the Major League Fishing Anglers Association Board.

You can follow him on Facebook and Instagram.